Friday, December 31, 2010

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

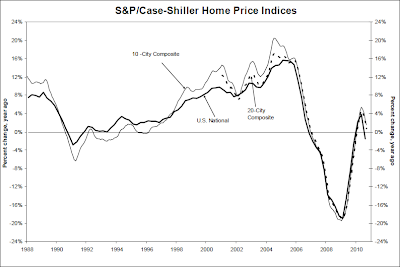

Home prices falling anew

S&P/Case-Shiller shows home prices dropping in all twenty cities tracked:

Home prices took a shockingly steep plunge on a monthly basis, an indication that the housing market could be on the verge of -- if it's not already in -- a double-dip slump.

Prices in 20 key cities fell 1.3% in October from a month earlier, an annualized decline of 15%, according to the S&P/Case-Shiller index released Tuesday. Prices were down 0.8% from 12 months earlier.

Month-over-month prices dropped in all 20 metro areas covered by the index. Six markets reached their lowest levels since the housing bust first began in 2006 and 2007.

Friday, December 24, 2010

Merry Christmas

Now you know why the U.S. Senate approved the New START treaty right before Christmas.

I'm on vacation for the next week or so. I'll be blogging again in the New Year.

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

Flat home prices expected for 2011

Economists expect home prices to be flat in 2011 after declining about 1% in 2010:

Home prices won’t show any year-over-year appreciation in 2011, according to the latest average of 110 forecasts from economists and housing analysts surveyed by MacroMarkets LLC.

The survey shows that economists expect home prices to fall by 0.17% in 2011 as measured by the S&P/Case-Shiller index of home prices in 20 U.S. cities. The average forecast for 2010 calls for the Case-Shiller index to ultimately show that home prices ended the year down 1.13%.

Overall, economists expect home prices to rise by 7.2% over the five-year period ending in 2014. In May, that forecast called for a 12% rise in prices over the span.

The effect of declining home prices on small business borrowing

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland has a new economic commentary on the declining housing bubble's effect on small business borrowing. Here's the conclusion:

Everyone agrees that small business borrowing declined during the recession and has not yet returned to pre-recession levels. Lesser consensus exists around the cause of the decline. Decreased demand for credit, declining creditworthiness of small business borrowers, an unwillingness of banks to lend money to small businesses, and tightened regulatory standards on bank loans have all been offered as explanations.

While we would agree that these factors have had an effect on the decline in small business borrowing through commercial lending, we believe that other limits on the credit of small business borrowers are also at play and could be harder to offset. Specifically, the decline in home values has constrained the ability of small business owners to obtain the credit they need to finance their businesses.

Of course, not all small businesses have been equally affected by the decline in home prices. While many small business owners use residential real estate to finance businesses, not all do. Those more likely do so to include companies in the real estate and construction industries, those located in the states with the largest increases in home prices during the boom, younger and smaller businesses, companies with lesser financial prospects, and those not planning to borrow from banks. These patterns are also evident in the data sources we examined.

The link between home prices and small business credit poses important challenges for policy makers seeking to improve small business owners’ access to credit. The solution is far more complicated than telling bankers to lend more or reducing the regulatory constraints that may have caused them to cut back on their lending to small companies. Returning small business owners to pre-recession levels of credit access will require an increase in home prices or a weaning of small business owners from the use of home equity as a source of financing. Neither of those alternatives falls into the category of easy and quick solutions.

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Lunar eclipse photo

Here's a photo I just took of tonight's lunar eclipse. The eclipse is still occurring as I write this.

Monday, December 20, 2010

What about the Silent Generation?

In discussing a new Pew Research Center study finding that Baby Boomers are feeling gloomier than other generations, CNN makes a glaring error:

The baby boomers are the generation of Americans born after World War II. What Tom Brokaw called the "greatest generation" is the generation that was in early adulthood during the Great Depression and World War II, and participated in the war effort. In between not being born and adulthood is an period called "childhood."

Americans who experienced childhood during the Great Depression or World War II are known as the "silent generation." They are too old to be baby boomers and too young to have participated in World War II. The silent generation is what makes up most of today's senior citizens, since the greatest generation has been gradually dying off for a while now.

This error was made by CNN, not the Pew Research Center.

Of course, I should point out that what we call a generation in societal terms is generally somewhat shorter than a generation in biological terms. A true generation should be about 25 years, because that's roughly the age that people in developed countries have children. But in cultural and societal terms, generations are defined by the common experiences of people within a certain age range. These common experiences are generally delineated by external events that don't neatly map to 25-year intervals.

"Most Americans are pretty glum three years into a Great Recession and a jobless recovery, but even in that context, the baby boomers stand out," said Paul Taylor, co-author of the study and vice president of the center.The "greatest generation" is not the generation that came right before the baby boomers.

In contrast, the study found only 60% of millennials — individuals between the ages of 18 and 29 — had a bleak view of the way things are going today.

And about 76% of respondents older than baby boomers, also called the "greatest generation," were dissatisfied with the status quo.

The baby boomers are the generation of Americans born after World War II. What Tom Brokaw called the "greatest generation" is the generation that was in early adulthood during the Great Depression and World War II, and participated in the war effort. In between not being born and adulthood is an period called "childhood."

Americans who experienced childhood during the Great Depression or World War II are known as the "silent generation." They are too old to be baby boomers and too young to have participated in World War II. The silent generation is what makes up most of today's senior citizens, since the greatest generation has been gradually dying off for a while now.

This error was made by CNN, not the Pew Research Center.

Of course, I should point out that what we call a generation in societal terms is generally somewhat shorter than a generation in biological terms. A true generation should be about 25 years, because that's roughly the age that people in developed countries have children. But in cultural and societal terms, generations are defined by the common experiences of people within a certain age range. These common experiences are generally delineated by external events that don't neatly map to 25-year intervals.

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Did cheap credit and easy lending cause the housing bubble? No!

Research by Edward L. Glaeser and Joshua D. Gottlieb of Harvard University, and Joseph Gyourko of the University of Pennsylvania argues that the housing bubble was not primarily caused by cheap credit and easy lending.

Abstract:

Unlike most people (including politicians and journalists who dare not blame the voters/viewers), I remember the home owners during the bubble who insisted I should buy a home because real estate is such a great investment. I remember them telling me how much their home had gone up in value. I remember them telling me I was throwing money out the window by renting. I remember being kicked out of my home because of a (failed) condo conversion by real estate investors chasing the rising prices. This is the psychology that causes bubbles! Since the collapse of the bubble, however, home buyers cannot be blamed. THEY WERE DECEIVED! THEY WERE CHEATED! Instead, they look for a scapegoat (greedy bankers) to blame for their own greedy decisions. This paper essentially says the banksters ain't to blame.

As for the initial fundamental cause of the rise in home prices, I've been going with the Bernanke explanation of a global savings glut, but this paper seems to throw a monkey wrench into that one.

Abstract:

Between 1996 and 2006, real housing prices rose by 53 percent according to the Federal Housing Finance Agency price index. One explanation of this boom is that it was caused by easy credit in the form of low real interest rates, high loan-to-value levels and permissive mortgage approvals. We revisit the standard user cost model of housing prices and conclude that the predicted impact of interest rates on prices is much lower once the model is generalized to include mean-reverting interest rates, mobility, prepayment, elastic housing supply, and credit-constrained home buyers. The modest predicted impact of interest rates on prices is in line with empirical estimates, and it suggests that lower real rates can explain only one-fifth of the rise in prices from 1996 to 2006. We also find no convincing evidence that changes in approval rates or loan-to-value levels can explain the bulk of the changes in house prices, but definitive judgments on those mechanisms cannot be made without better corrections for the endogeneity of borrowers’ decisions to apply for mortgages.Conclusion:

Interest rates do influence house prices, but they cannot provide anything close to a complete explanation of the great housing market gyrations between 1996 and 2010. Over the long 1996-2006 boom, they cannot account for more than one-fifth of the rise in house prices. Their biggest predictive influence is during the 2000-2005 period, when long rates fell by almost 200 basis points. That can account for about 45% of the run-up in home values nationally during that half-decade span. However, if one is going to cherry-pick time periods, it also must be noted that falling real rates during the 2006-2008 price bust simply cannot account for the 10% decline in FHFA indexes those years.This is essentially what I've been arguing from the beginning: The bubble was primarily the fault of home buyers who saw real estate as a way to get rich quick. Some fundamental factor in the late 1990s caused the initial rise in home prices, but then psychology (greed) took over and home buyers were willing to pay any price for a home because "real estate is the best investment you can make" and "home prices never go down." (If something is the best investment you can make and the price will never go down, then the price you pay doesn't matter.)

There is no convincing evidence from the data that approval rates or down payment requirements can explain most or all of the movement in house prices either. The aggregate data on these variables show no trend increase in approval rates or trend decrease in down payment requirements during the long boom in prices from 1996-2006. However, the number of applications and actual borrowers did trend up over this period (and fall sharply during the bust), which raises the possibility that the nature of the marginal buyer was changing over time. Carefully controlling for that requires better and different data, so our results need not be the final word on these two credit market traits.

This leaves us in the uncomfortable position of claiming that one plausible explanation for the house price boom and bust, the rise and fall of easy credit, cannot account for the majority of the price changes, without being able to offer a compelling alternative hypothesis. The work of Case and Shiller (2003) suggests that home buyers had wildly unrealistic expectations about future price appreciation during the boom. They report that 83 to 95 percent of purchasers in 2003 thought that prices would rise by an average of around 9 percent per year over the next decade. It is easy to imagine that such exuberance played a significant role in fueling the boom.

Yet, even if Case and Shiller are correct, and over-optimism was critical, this merely pushes the puzzle back a step. Why were buyers so overly optimistic about prices? Why did that optimism show up during the early years of the past decade and why did it show up in some markets but not others? Irrational expectations are clearly not exogenous, so what explains them? This seems like a pressing topic for future research.

Moreover, since we do not understand the process that creates and sustains irrational beliefs, we cannot be confident that a different interest rate policy wouldn’t have stopped the bubble at some earlier stage. It is certainly conceivable that a sharp rise in interest rates in 2004 would have let the air out of the bubble. But this is mere speculation that only highlights the need for further research focusing on the interplay between bubbles, beliefs and credit market conditions.

Unlike most people (including politicians and journalists who dare not blame the voters/viewers), I remember the home owners during the bubble who insisted I should buy a home because real estate is such a great investment. I remember them telling me how much their home had gone up in value. I remember them telling me I was throwing money out the window by renting. I remember being kicked out of my home because of a (failed) condo conversion by real estate investors chasing the rising prices. This is the psychology that causes bubbles! Since the collapse of the bubble, however, home buyers cannot be blamed. THEY WERE DECEIVED! THEY WERE CHEATED! Instead, they look for a scapegoat (greedy bankers) to blame for their own greedy decisions. This paper essentially says the banksters ain't to blame.

As for the initial fundamental cause of the rise in home prices, I've been going with the Bernanke explanation of a global savings glut, but this paper seems to throw a monkey wrench into that one.

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

What factors create better schools? Lessons from the international tests...

Asia-Pacific economies absolutely dominated the most recent PISA international student assessment tests.

Shanghai, China took the top spot in all three subject areas—reading, math, and science. Other Asia-Pacific outperformers were South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, New Zealand, Japan and Australia.

Our neighbor to the north, Canada, also outperformed the international average in all three subject areas. The United States, however, was mediocre. So were the big five European Union countries—Germany, France, United Kingdom, Italy and Spain.

Here are some finding from the OECD about what causes educational outperformance:

Shanghai, China took the top spot in all three subject areas—reading, math, and science. Other Asia-Pacific outperformers were South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, New Zealand, Japan and Australia.

Our neighbor to the north, Canada, also outperformed the international average in all three subject areas. The United States, however, was mediocre. So were the big five European Union countries—Germany, France, United Kingdom, Italy and Spain.

Here are some finding from the OECD about what causes educational outperformance:

- Successful school systems provide all students, regardless of their socio-economic backgrounds, with similar opportunities to learn.

- Most successful school systems grant greater autonomy to individual schools to design curricula and establish assessment policies, but these school systems do not necessarily allow schools to compete for enrolment.

- School systems considered successful tend to prioritise teachers’ pay over smaller classes.

- The greater the prevalence of standards-based external examinations, the better the performance.

- Schools with better disciplinary climates, more positive behaviour among teachers and better teacher-student relations tend to achieve higher scores in reading.

- After accounting for the socio-economic and demographic profiles of students and schools, students in OECD countries who attend private schools show performance that is similar to that of students enrolled in public schools.

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Health insurance mandate ruled unconstitutional

Ilya Shapiro explains the constitutional significance:

Today is a good day for liberty. By striking down the unprecedented requirement that Americans buy health insurance — the "individual mandate" — Judge Henry Hudson vindicated the idea that ours is a government of delegated and enumerated, and thus limited, powers.

But this should not be surprising, for the Constitution does not grant the federal government the power to force private commercial transactions.

Even if the Supreme Court has broadened the scope of Congress' authority under the Commerce Clause — it can now reach local activities that have a substantial effect on interstate commerce — never before has it allowed people to face a civil penalty for declining to buy a particular product. Hudson found therefore that the individual mandate "is neither within the letter nor the spirit of the Constitution."

Stated another way, every exercise of Congress' power to regulate interstate commerce has involved some form of action or transaction engaged in by an individual or legal entity. The government's theory — that the decision not to buy insurance is an economic one that affects interstate commerce in various ways — would, for the first time ever, permit laws commanding people to engage in economic activity.

Under such a reading, which judges in two other cases have unfortunately adopted, nobody would ever be able to plausibly claim that the Constitution limits congressional power. The federal government would then have wide authority to require that Americans engage in activities ranging from eating spinach and joining gyms (in the health care realm) to buying GM cars. Congress could tell people what to study or what job to take...

As for the oft-invoked car insurance analogy, being required to buy insurance if you choose to drive is different from having to buy it because you are alive. And it is states that impose car insurance mandates, under their general police powers — which the federal government lacks. ...

As Hudson said, "Despite the laudable intentions of Congress in enacting a comprehensive and transformative health care regime, the legislative process must still operate within constitutional bounds. Salutatory goals and creative drafting have never been sufficient to offset an absence of enumerated powers."

Monday, December 13, 2010

Why "Saving the Earth" is stupid

Yes, climate change exists. And, yes, most climate scientists and environmental scientists believe it is primarily caused by human activity. And, yes, we should try to do something about it. But environmentalists are prone to exaggerated language. One of those exaggerations is the idea that preventing further global warming is "Saving the Earth."

Yes, climate change exists. And, yes, most climate scientists and environmental scientists believe it is primarily caused by human activity. And, yes, we should try to do something about it. But environmentalists are prone to exaggerated language. One of those exaggerations is the idea that preventing further global warming is "Saving the Earth."The Earth has been around for a long time. During that time it has been through quite a lot. It has been struck by multiple asteroids. It was once struck so violently that

Even during times when life existed, the Earth has been far warmer than it is today. The global climate was much warmer when the dinosaurs roamed the Earth than it is now. It was the global cooling that occurred after another asteroid strike around 65.5 million years ago that gave rise to warm-blooded mammals.

This graph shows estimated global temperatures during the Phanerozoic Eon, the period during which abundant animal life has existed on Earth. Notice that we are in one of the cooler periods.

Global warming is primarily a threat to mammals. (Remember, humans are mammals.) Under global warming, vegetation will thrive. So will cold-blooded animals such as insects and reptiles. Rising ocean levels will benefit fish as well. It is us, the mammals, who are at risk. As far as humans are concerned, it is primarily a risk to people in poor countries. Therefore, the environmentalist message shouldn't be "Save the Earth," it should be "Save the Mammals."

Global warming is primarily a threat to mammals. (Remember, humans are mammals.) Under global warming, vegetation will thrive. So will cold-blooded animals such as insects and reptiles. Rising ocean levels will benefit fish as well. It is us, the mammals, who are at risk. As far as humans are concerned, it is primarily a risk to people in poor countries. Therefore, the environmentalist message shouldn't be "Save the Earth," it should be "Save the Mammals."Minimizing global climate change may save many mammals, perhaps even humans. But fear not for the Earth! Regardless of its climate, it will continue to happily orbit the sun for billions of years to come.

Saturday, December 11, 2010

How Shanghai dominated the international student achievement test

On the most recent PISA international student assessment tests, Shanghai, China took the top spot in all three subject areas—reading, math, and science.

Here's how Shanghai, the top performer, gets its students to achieve:

Here's how Shanghai, the top performer, gets its students to achieve:

When the results of an international education assessment put Shanghai and several other Asian participants ahead of the US and much of Western Europe, many Americans were shocked. ...

Shanghai trounced the OECD average: in reading, it got a 556, versus a 493 OECD average; in science, the score was 575 versus 501; and in math, there was a difference of more than 100 points – a 600 in Shanghai versus a 496 average. ... The results left many observers with one question: How did they do it? ...

Experts ascribe Shanghai’s success to China's assessment that academic achievement is foremost the result of hard work rather than a good teacher or innate talent.

“Students not only work harder, but they attribute their academic success to their own work,” says James Stigler, a professor of psychology at UCLA who has conducted research on the Chinese educational system. “Chinese students say the most important factor is studying hard. They really believe that’s the root of success in learning.”

That emphasis on hard work is complemented by several other key practices: active engagement by parents, early efforts to build up attention spans, and families' emphasis on spending long hours in school and on homework while doing little else. ...

Dr. Miller, a longtime observer of the Chinese educational system, has seen sweeping differences in the classroom.

In one study, he sat in first-grade math classes in the US and in Beijing and tracked the number of students who were paying attention throughout the lesson. At the end, about 90 percent of Chinese first graders were still following the lesson. Only about half of the Americans were.

The phenomenon was noted in the PISA report as well: “Typically in a Shanghai classroom, students are fully occupied and fully engaged. Non-attentive students are not tolerated,” it said.

The difference in instructional techniques plays a big role, Miller says. Chinese teachers tended to spend a long time giving instructions in the beginning, while American teachers gave cursory instructions then corrected students as the lesson continued. American students’ attention wandered when they became confused.

Another difference, particularly in math instruction, stood out to both Dr. Stigler and Miller. The US teaches procedurally in math, they noted – repetition of the same procedures until a student can remember reflexively how to solve a particular type of math problem. In China, students are encouraged to understand the connections between each step of the problem so that they can think their way through them, even if the order is forgotten.

In the US, we “do things over and over again until they sink in,” Miller says. “You don’t really know something until you can explain why you do this, why you don’t do that.”

Once one student in the classroom explains a problem correctly, the next student has to explain it, too. That is often repeated until most or all of the students can confidently work their way through a problem, Miller says. It’s a bit different from the US practice of calling on one or two raised hands, then moving on.

Friday, December 10, 2010

Four more years of housing stagnation expected

RealtyTrac and Trulia expect continuing housing market stagnation:

The housing market will remain depressed, with record high foreclosure levels, rising mortgage rates and a glut of distressed properties dampening the market for years to come, industry experts predicted on Tuesday.

"We don't see a full market recovery until 2014," said Rick Sharga of RealtyTrac, a foreclosure marketplace and tracking service. He said that he expected more than 3 million homeowners to receive foreclosure notices in 2010, with more than 1 million homes being seized by banks before the end of the year.

Both of those numbers are records and expected to go even higher, as $300 billion in adjustable rate loans reset and foreclosures that had been held up by the robo-signing scandal work through the process. That should make the first quarter of 2011 even uglier than the fourth quarter of 2010, he said. ...

Mortgage rates will start to rise in 2011, further dampening demand and limiting affordability, said Pete Flint, chief executive of Trulia.com, a real estate search and research website. "Nationally, prices will decline between 5 percent and 7 percent, with most of the decline occurring in the first half of next year," he said.

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Green jobs training: The road to unemployment

Green jobs are political marketing, not reality. Workers who believed the hype and retrained for these largely non-existent jobs are finding themselves unemployable:

Green jobs are political marketing, not reality. Workers who believed the hype and retrained for these largely non-existent jobs are finding themselves unemployable:After losing his way in the old economy, Laurance Anton tried to assure his place in the new one by signing up for green jobs training earlier this year at his local community college.If you don't substantially raise the price of carbon, people will continue to get the vast majority of their energy from fossil fuels. Even if you do substantially raise the cost of fossil fuels, the "green jobs" created will likely be less than the "black jobs" lost.* That's because energy conservation—using less energy—is an essential part of reducing carbon emissions. Using less energy means that the energy industry must shrink as a percentage of GDP, while other industries grow as a percentage of GDP. The "black jobs" lost would be completely offset by more jobs elsewhere in the economy, but it is a mistake to assume that they would all be in green jobs. Many of them will be in other industries entirely.

Anton has been out of work since 2008, when his job as a surveyor vanished with Florida's once-sizzling housing market. After a futile search, at age 56 he reluctantly returned to school to learn the kind of job skills the Obama administration is wagering will soon fuel an employment boom: solar installation, sustainable landscape design, recycling and green demolition.

Anton said the classes, funded with a $2.9 million federal grant to Ocala's workforce development organization, have taught him a lot. He's learned how to apply Ohm's law, how to solder tiny components on circuit boards and how to disassemble rather than demolish a building.

The only problem is that his new skills have not resulted in a single job offer. Officials who run Ocala's green jobs training program say the same is true for three-quarters of their first 100 graduates.

"I think I have put in 200 applications," said Anton, who exhausted his unemployment benefits months ago and now relies on food stamps and his dwindling savings to survive. "I'm long past the point where I need some regular income." ...

The industry's growth has been undercut by the simple economic fact that fossil fuels remain cheaper than renewables.

The Obama administration has completely missed its opportunity to raise the price of carbon. If it didn't happen when Democrats controlled the House of Representatives, it won't happen with Republicans in control. Democrats seem to think that reducing carbon emissions, fighting global warming, creating "green jobs," and promoting "energy independence" can occur completely through wishful thinking. It cannot. The price of carbon must go up.

Hat tip: Jeffrey Miron

* Since oil, coal, and soot are black, I figure "black jobs" is the best complementary term to "green jobs."

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

CNBC housing debate

In the video, Susan Wachter is misleading. Price-to-rent ratios are out of line, not just by 1890 levels, but also by 1970-1999 levels—basically all of the pre-bubble period. From 2007-2008, prices were falling rapidly until the Federal government stepped in to prop them up.

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

Tea Party leader: Renters should have no right to vote

Judson Phillips, the president of Tea Party Nation, on renters' right to vote:

The Founding Fathers originally said they put certain restrictions on who got the right to vote. It wasn’t you were just a citizen and you automatically got to vote. Some of the restrictions, you know, you obviously would not think about today. But one of them was you had to be a property owner. And that makes a lot of sense, because if you’re a property owner you actually have a vested stake in the community. If you’re not a property owner, you know, I’m sorry but property owners have a little bit more of a vested stake in the community than non-property owners do.And many libertarians think the Tea Party is a pro-liberty movement?! It's not. It's an anti-libertarian, social conservative movement.

Monday, December 6, 2010

Thoughts on unemployment insurance and the mean duration of unemployment

Harvard economics professor Greg Mankiw provides his thoughts on the optimal duration of unemployment insurance (UI) during an economic downturn:

The median duration of unemployment is currently 21.6 weeks. That means 50% of all unemployed workers are finding jobs within that span of time. (By comparison, the mean is currently 33.8 weeks.) When half of all unemployed workers find jobs within 21.6 weeks, providing 99 weeks of unemployment insurance seems a bit excessive to me. Sure, some people are naturally more employable than others. The less education people have, the higher their chances of being unemployed. College graduates probably find new jobs quickly while high school dropouts take much longer. For this reason, the mean is probably a better guide than the median.

I'll suggest a simple policy rule:

The length of unemployment insurance should automatically adjust throughout the business cycle. It should provide full benefits until 1x the mean duration of unemployment, then decline [not necessarily linearly] until being discontinued at 2x the mean duration of unemployment.

Because the mean duration of unemployment is considerably longer than the median, this will provide most unemployed workers with full unemployment benefits during the entire time they're unemployed. Those workers who don't find jobs will gradually be given stronger economic incentives to look harder and lower their standards. Workers who are still unemployed after 2x the mean duration of unemployment are significant outliers, and would be cut off, although welfare may still be available to them if they truly need it.

A downside to the rule above as stated is that it will tend to hit poorly-educated workers the hardest, because they are less employable than most workers. I'm not dogmatic about the rule. It's really just a suggestion. A simpler and more generous version would provide full benefits until 2x the mean duration of unemployment, ending with a sharp cutoff point. The key is that the length of unemployment insurance benefits should automatically adjust throughout the business cycle, using mean (preferably) or median duration of unemployment as a guide.

Let me also suggest a second policy rule:

The amount (i.e. dollars per week) of unemployment insurance benefits people receive should also vary throughout the business cycle. The amount they get should automatically go up or down in inverse proportion to the output gap, with the default level assuming an output gap of zero.

With this second policy rule, when the economy is weak payment amounts would go up, providing an extra economic stimulus; when the economy is strong, payment amounts would go down to incentivize the unemployed to take one of the many jobs available.

Update: Bentley University economics professor Scott Sumner writes in:

UI has pros and cons. The pros are that it reduces households' income uncertainty and that it props up aggregate demand when the economy goes into a downturn. The cons are that it has a budgetary cost (and thus, other things equal, means higher tax rates now or later) and that it reduces the job search efforts of the unemployed. To me, all these pros and cons seem significant. I have yet to see a compelling quantitative analysis of the pros and cons that informs me about how generous the optimal system would be.The thought I've been kicking around recently is that the length of unemployment insurance should automatically adjust based on either the mean or median duration of unemployment. My hypothesis is that the economic optimum is likely within the range of 1x and 2x the mean (average) duration of unemployment.

So when I hear economists advocate the extension of UI to 99 weeks, I am tempted to ask, would you also favor a further extension to 199 weeks, or 299 weeks, or 1099 weeks? If 99 weeks is better than 26 weeks, but 199 is too much, how do you know?

It is plausible to me that UI benefits should last longer when the economy is weak. The need for increased aggregate demand is greater, and the impact on job search may be weaker. But this conclusion is hardly enough to tell us whether 99 weeks is too much, too little, or about right.

The median duration of unemployment is currently 21.6 weeks. That means 50% of all unemployed workers are finding jobs within that span of time. (By comparison, the mean is currently 33.8 weeks.) When half of all unemployed workers find jobs within 21.6 weeks, providing 99 weeks of unemployment insurance seems a bit excessive to me. Sure, some people are naturally more employable than others. The less education people have, the higher their chances of being unemployed. College graduates probably find new jobs quickly while high school dropouts take much longer. For this reason, the mean is probably a better guide than the median.

I'll suggest a simple policy rule:

The length of unemployment insurance should automatically adjust throughout the business cycle. It should provide full benefits until 1x the mean duration of unemployment, then decline [not necessarily linearly] until being discontinued at 2x the mean duration of unemployment.

Because the mean duration of unemployment is considerably longer than the median, this will provide most unemployed workers with full unemployment benefits during the entire time they're unemployed. Those workers who don't find jobs will gradually be given stronger economic incentives to look harder and lower their standards. Workers who are still unemployed after 2x the mean duration of unemployment are significant outliers, and would be cut off, although welfare may still be available to them if they truly need it.

A downside to the rule above as stated is that it will tend to hit poorly-educated workers the hardest, because they are less employable than most workers. I'm not dogmatic about the rule. It's really just a suggestion. A simpler and more generous version would provide full benefits until 2x the mean duration of unemployment, ending with a sharp cutoff point. The key is that the length of unemployment insurance benefits should automatically adjust throughout the business cycle, using mean (preferably) or median duration of unemployment as a guide.

Let me also suggest a second policy rule:

The amount (i.e. dollars per week) of unemployment insurance benefits people receive should also vary throughout the business cycle. The amount they get should automatically go up or down in inverse proportion to the output gap, with the default level assuming an output gap of zero.

With this second policy rule, when the economy is weak payment amounts would go up, providing an extra economic stimulus; when the economy is strong, payment amounts would go down to incentivize the unemployed to take one of the many jobs available.

Update: Bentley University economics professor Scott Sumner writes in:

I favor a self insurance approach. Each worker contributes 10% of their income into a private UI account, which they can draw from when unemployed. Any funds not used can be allocated to retirement. This avoids the problem of UI acting as a disincentive to find work.

Sunday, December 5, 2010

2010 is one of the warmest years on record so far

The first eleven months of 2010 are leading it to be one of the warmest years on record:

The first eleven months of 2010 are leading it to be one of the warmest years on record:This year is on track to enter the almanac as one of the three warmest years on record globally, along with 1998 and 2005, according to a preliminary analysis by the World Meteorological Organization.The public debate about climate change is so intertwined with politics that I try to avoid politically-motivated arguments on the subject. I've never watched Al Gore's documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, because he's an environmental activist, not a climate scientist. I prefer to get my information from reputable scientific sources such as the National Academy of Science. Instead of An Inconvenient Truth, I watched the Teaching Company DVD series Earth's Changing Climate by Prof. Richard Wolfson of Middlebury College, available at your local library. These sources concur with the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, but are not as alarmist as environmental activists.

Not only that, but 2010 stands a decent chance of capturing the record, depending on temperature data from November and December, according to Michel Jarraud, secretary-general of the WMO. Global average temperatures for the first 10 months of the year are running slightly ahead of those for the same period in '98 and '05...

Preliminary temperature data for November are comparable to temperatures seen in November 2005, indicating they have remained near record levels as the year winds down.

Even if 2010 fails to capture the top spot, the first decade of the 21st century already has gone into the books as the warmest since 1850, when the instrument record began. ...

Some climate scientists caution that any one year's worth of events is driven more by natural variability than by long-term warming triggered by the released of carbon dioxide from burning fossils fuel. But when 2010's extreme events are seen in that broader context, they appear to fit long-term patterns the climate models have generally projected for a climate system responding to increasing atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases.

A range of studies have documented an increase in extreme heat events, a decrease in extreme cold events, and an increase in rainfall and snowfall intensity globally during the past 50 years...

Republicans attack the IPCC as biased, but the IPCC is not alone in its conclusions. As Science Magazine, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, once stated:

IPCC is not alone in its conclusions. In recent years, all major scientific bodies in the United States whose members' expertise bears directly on the matter have issued similar statements. ... Politicians, economists, journalists, and others may have the impression of confusion, disagreement, or discord among climate scientists, but that impression is incorrect.Here's a graph of global temperatures from 1850-2008:

Knowing that anthropological climate change exists and doing something productive about it are two different issues. Harvard economist Greg Mankiw has a simple solution. Raise carbon taxes, and then reduce other taxes so that the overall tax burden on the American economy doesn't change.

Knowing that anthropological climate change exists and doing something productive about it are two different issues. Harvard economist Greg Mankiw has a simple solution. Raise carbon taxes, and then reduce other taxes so that the overall tax burden on the American economy doesn't change.

Saturday, December 4, 2010

Ron Paul defends Wikileaks... and freedom

Congressman Ron Paul defends Wikileaks:

Congressman Ron Paul defends Wikileaks:In a free society we're supposed to know the truth. In a society where truth becomes treason, then we're in big trouble. And now, people who are revealing the truth are getting into trouble for it.The people attacking Wikileaks—and calling for the murder of its founder—are the enemies of freedom.

Thursday, December 2, 2010

House hunters afraid to buy

From CNNMoney:

One reason mortgage interest rates are so low is because inflation is abnormally low, so real mortgage rates aren't as low as they appear. In fact, we currently have the lowest level of core inflation on record. Here's a graph:

Despite some of the best home-buying conditions in years— affordable prices, low interest rates and lots of choices — fear of buying has infected the market.Despite what the real estate cheerleading in the article would leave you to believe, there's still a housing bubble. In much of the U.S., homes are still overvalued. There's good reason not to buy.

It has paralyzed house hunters, making them unable to pull the trigger even on attractive deals. Some are worried about making the payments, while others are convinced they'll save even more if they wait.

It's perfectly natural that they should feel that way in the wake of the housing bust, said Lawrence Yun, the chief economist for the National Association of Realtors. "It's like when the stock market is crashing," he said. "People are waiting to see if deals will get better."

In fact, home sales are down by about 25% from last year, which means a lot of people are sitting on the sidelines. And real estate agents are having to get used to the fear of buying trend.

One reason mortgage interest rates are so low is because inflation is abnormally low, so real mortgage rates aren't as low as they appear. In fact, we currently have the lowest level of core inflation on record. Here's a graph:

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

U.S. house prices fell 1.5% in Q3 2010

According to S&P/Case-Shiller, U.S. house prices fell 1.5% in the third quarter of 2010 compared to a year earlier:

Data through September 2010, released today by Standard & Poor’s for its S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices, the leading measure of U.S. home prices, show that the U.S. National Home Price Index declined 2.0% in the third quarter of 2010, after having risen 4.7% in the second quarter. Nationally, home prices are 1.5% below their year-earlier levels. In September, 18 of the 20 MSAs covered by S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices and both monthly composites were down; and only the two composites and five MSAs showed year-over-year gains. While housing prices are still above their spring 2009 lows, the end of the tax incentives and still active foreclosures appear to be weighing down the market.

The chart above depicts the annual returns of the U.S. National, the 10-City Composite and the 20-City Composite Home Price Indices. The S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index, which covers all nine U.S. census divisions, recorded a 1.5% decline in the third quarter of 2010 over the third quarter of 2009. In September, the 10-City and 20-City Composites recorded annual returns of +1.6% and +0.6%, respectively. These two indices are reported at a monthly frequency and September was the fourth consecutive month where the annual growth rates moderated from their prior month’s pace, confirming a clear deceleration in home price returns.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)